[There are no entries for August 1726.]

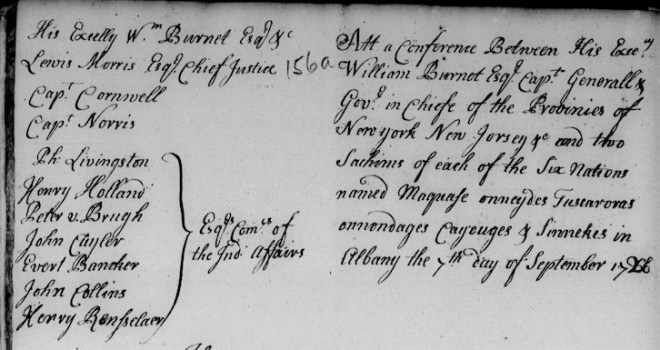

In preparation for the conference held September 7-14, Governor William Burnet issued a proclamation that prohibited giving liquor to Indians or trading in Indian goods to be used as presents, thus maintaining control over goods that might influence native decision makers. The proceedings printed in Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York, Volume 5, beginning on page 786, are substantially the same as the version in the records of the Indian Commissioners. I have not transcribed them, but they are summarized below. DRCHNY also includes a letter that Governor Burnet sent to the Lords of Trade (p. 783 et seq.) along with the treaty, in which he explains that his main goal was to prevent the Six Nations from authorizing the French fort at Niagara. He added some related correspondence between himself and the Governor of Montreal and a questionable deed to Seneca, Cayuga, and Onondaga lands (DRCHNY 5:800) negotiated secretly with a small group of sachims at the end of the conference. The deed is not part of the records of the Indian Commissioners.

In preparation for the conference held September 7-14, Governor William Burnet issued a proclamation that prohibited giving liquor to Indians or trading in Indian goods to be used as presents, thus maintaining control over goods that might influence native decision makers. The proceedings printed in Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York, Volume 5, beginning on page 786, are substantially the same as the version in the records of the Indian Commissioners. I have not transcribed them, but they are summarized below. DRCHNY also includes a letter that Governor Burnet sent to the Lords of Trade (p. 783 et seq.) along with the treaty, in which he explains that his main goal was to prevent the Six Nations from authorizing the French fort at Niagara. He added some related correspondence between himself and the Governor of Montreal and a questionable deed to Seneca, Cayuga, and Onondaga lands (DRCHNY 5:800) negotiated secretly with a small group of sachims at the end of the conference. The deed is not part of the records of the Indian Commissioners.

On September 7th Governor Burnet held a private meeting with his staff and a small group of two sachems from each of the Six Nations. Part of the record of this meeting is written out as a series of queries and answers, a different format from the usual one in which wampum belts were presented on specific points and the other side would consider them before responding to them as a group. Burnet, or whoever wrote up the minutes of the meeting, may have structured it this way in order to create a record that supported the idea that the Six Nations were subject to British dominion and the governor could query them as he would do with a subordinate official.

At the private meeting, the Onondaga speaker Ajewachta recounted how the French envoy “Monsieur Longueuil” (Charles Le Moyne de Longueuil, 1687-1755) had presented the building at Niagara as a trading house to replace an existing bark house that had fallen into disrepair. According to Ajewachta, the Onondagas agreed to it despite objections from the Senecas who actually owned the land. Ajewachta tried to reassure Governor Burnet that the region encompassing Niagara and Lake Ontario, would remain “a path of peace for all christians and Indians to come and go forward and backward on account of Trade.” He said the Six Nations told the French that they held firm to the alliance with the English as well as to peace with the French. They wanted the French and the English to settle any disagreements “at Sea and not in [the Six Nations’] Country.”

When Governor Burnet asked the sachims whether they were not sorry that they had agreed to the new building at Niagara, they said Longueil had won them over but they immediately regretted it. They described the extensive negotiations between them and the French in which the Onondagas had tentatively agreed to the French request., but subject to the approval of the rest of the Six Nations and void if they disallowed it. A Seneca Sachim named Kanakarichton verified that the land at Niagara belonged to the Senecas along with land on the other side of the lake. Nonetheless, the French who came to build the fort insisted on finishing it even while the Six Nations were still discussing the situation with the French governor through the interpreter Jean Coeur (Louis-Thomas Chabert de Joncaire). When the building was finished it would be staffed by 30 soldiers as well as officers and a priest.

The Six Nations also said they had heard that two Frenchmen had asked an unidentified nation living on the Ohio River to take up the hatchet against the Six Nations on behalf of the French, but that nation had refused. The Frenchmen told them that papers were going to circulate to Philadelphia, New York, Albany, and Montreal about an agreement between the French and the English to cut off their nation once the fort at Niagara was complete, but the warriors burned the papers, preventing it. They also heard ominous things from Canada about proceedings between the French and the English, and asked Governor Burnet what news he had heard. Finally they said the traders in their country were cheating them by selling water disguised as rum that went bad in a day or two.

Governor Burnet promised to send someone to oversee the trade to prevent cheating. He explained that France and Great Britain were currently allies who were going to war with Spain. He read them the text of a letter that he had sent to the governor of Canada about the Treaty of Utrecht, which required the French in Canada not to hinder or molest the five Nations or their allies and guaranteed free trade for all. After Governor Burnet encouraged them to do so, the 12 sachims asked him to contact King George and request him to write the King of France to object to Fort Niagara. Burnet closed the meeting by stating that what had transpired would now be stated publicly.

Two days later proceedings resumed with a full gathering of all the representatives of the Six Nations, Governor Burnet, the Commissioners for Indian Affairs, and aldermen from the City of Albany. Governor Burnet, who had been studying the French works on the subject, reviewed in detail the history of the wars between France, its native allies, and the Six Nations, as well as their peaceful relations with the English. He told them that the King of Great Britain was their “true father” who had always fed and cloathed them and provided them with arms. He renewed the Covenant Chain and gave them a belt of wampum.

Governor Burnet told the gathering that Monsieur Longueuil (Charles Le Moyne de Longueuil, 1656-1729, Governor of Montreal, whose son of the same name was in charge of Fort Niagara) had sent him a letter claiming that the Six Nations had unanimously agreed to the new fort at Niagara, but the Six Nations now said they were afraid the fort would enable the French to keep them from their hunting grounds and prevent the far nations from coming to trade. He explained the free trade provisions of the Treaty of Utrecht and said he would convey the Six Nations’ complaints about Fort Niagara to King George, who would ask the King of France to review whether it violated the Treaty of Utrecht. If the fort was in violation it should be removed.

Governor Burnet also said that when he conveyed a request from the Six Nations to the governor of Virginia to set up a meeting, Virginia and South Carolina had complained about attacks on their frontiers by Tuscaroras and others. Burnet asked that the offenders be punished. In particular the Senecas attacked an English trading house called Constichrohare at Characks (Cheraw) and captured an Indian boy who was the slave of Nathaniel Ford along with guns, blankets and powder. The goods and the Indian slave should be delivered to Peter Barbarie, who would reimburse the captors in the name of the owner. Burnet asked the Six Nations not to allow “French Indians” to pass through their country in order to attack the southern colonies.

Kanakarighton responded for the Six Nations. After renewing the Covenant Chain, he said that the Six Nations had already asked the Governor of Canada to stop building the fort at Niagara. They now came to the English “howling” because the French were building on their land. He presented a belt to the governor and asked him to write to King George as soon as possible to have the fort removed.

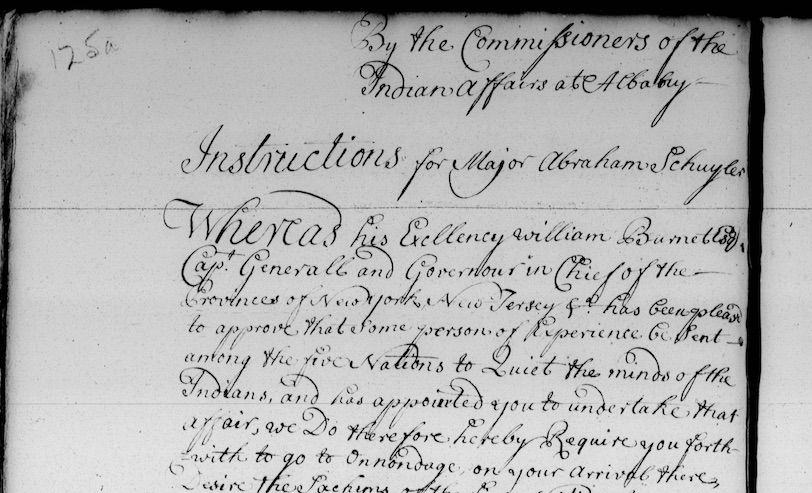

Kanakarighton notified Governor Burnet that Jean Coeur was expected soon at Onondaga, where he would probably spread negative rumors about the English. He asked Burnet to send a “Man of Experience” to Onondaga to hold a meeting with Jean Coeur in front of the Six Nations. It should be conducted speaking “nothing but Indian between the brother Corlaer and the French, every one to answer for himself concerning what ill Reports he shall have spread” in order to get to the truth and “know who is the lyar.”

Kanakarighton acknowledged Burnet’s concerns about frontier attacks on Virginia and South Carolina. He said that Senecas, Mohawks, Tuscaroras, and “French Indians” were all involved, but their intention was only to pursue Indian enemies present in the trading house that was attacked. The slave that Governor Burnet wanted returned had been given to “Indians who live on a Branch of Susquehannah River, which is called Soghniejadie.” He suggested that the English look for him there themselves because the place was “nearer to you than us” (probably meaning nearer to Virginia.) He asked that the attacks be forgiven as merely accidents committed without the approval of the sachems and agreed to try to stop French Indians to travel through Iroquoia to go fighting. He pointed out that the English must do their part “for many go fighting thro’ Albany to the English Settlements, who do not come thro’ the Six Nations.

Kanakarighton concluded by adding to what Burnet had said about the history of relations between the Six Nations and the English. They arose through trade at a time when goods were cheap, but now goods had become expensive. He asked for cheaper prices, especially for powder. Moreover, now that the Six Nations had agreed to let the English trade (“place Beaver Traps”) on the Onondaga River, they had been deceived, since traders there sold river water as rum for a high price. But instead of asking for better rum, he asked for no rum, since it was causing quarrels between married couples and between young Indians and sachims. When Indians from beyond Iroquoia wanted rum, they should come to Albany for it as they used to do, while traders to the Six Nations should bring powder and Indian goods for the same price as they would cost at Albany.

Finally he conveyed a request from the Senecas that Myndert Wemp return to their country as a smith along with an armorer, Andries Nak, who should be taught to speak their language.

Governor Burnet agreed to ask King George to persuade the King of France to remove Fort Niagara. He did not agree to send a representative to Onondaga for a meeting with Joncaire, claiming that the Six Nations’ own experience should be enough to show that French reports about the English were false. However, he said he would send someone to the Senecas for the winter to address their concerns. He said he would tell the governor of Virginia what the Six Nations asked (that frontier incidents be forgiven) but the best way to prevent Virginia from taking up the hatchet was to stop such attacks. Burnet said he could not control what merchants charged for their goods, and refused to stop selling rum on the Onondaga River. However, he would post someone there to oversee the trade and prevent cheating, and would ask Myndert Wemp to return to the Seneca country as a smith along with an armorer. He wished them a good journey home, told them he was providing them with a “noble Present” from the king, and explained that rum and provisions would be given to them for their journey after they were “past Schenectady.”

Burnet also held a brief conference with the River (Mohican) and Schaghticoke Indians the same day, condoling two sachims who had died, and recommending Wawiachech to replace them, renewing the Covenant Chain, and admonishing them to stay at Schaghticoke and not go to Canada. They thanked him and explained that the people who left for Canada were fleeing debts, but those who remained would live and die at Schaghticoke.

On September 14th Burnet held another private conference, this time with two sachims each from the Senecas and Onondagas and three from the Cayugas, but no Oneidas, Tuscaroras, or Mohawks. The names of those who attended are given as Kanakarighton, Thanintsoronwee, Ottsochkooree, DeKanisoree, Aenjeweerat, Kackjakadorodon, and Sadekeenaghtie. Going considerably beyond what had been discussed in the full conference, the small group consented to Governor Burnet’s suggestion that they sign what Burnet called a “deed of surrender” putting their land in trust to the King of England to be protected for the use of their nations.

A deed was signed, becoming part of the “Original Roll in the Secretary of State’s Office” in Albany and later printed in DRCHNY 5:800. No copy was kept in the records of the Commissioners of Indian Affairs, which generally did not include deeds. Peter Wraxall was not aware of the deed when he wrote his Abridgement, which discusses the September 1726 conference on p. 168-169.

In his letter to the Lords of Trade sent with the treaty, (DRCHNY 5:783-785) Governor Burnet explained that he did not tell the Mohawks or Oneidas about the September 14th meeting, since their lands were not at issue and if he told them the French might learn about it sooner. Burnet told the Lords of Trade that he pursuaded the New York Assembly to agree to his proposal to build an English fort at the mouth of the Onondaga River (Oswego). Once it was built he intended to meet the Indians again and get them to publicly confirm the deed, which “some of them have signed.” Thus he acknowledged that it required further confirmation. The deed surrenders the land to be “protected & Defended” by the king for the use of the three nations. It says nothing about building forts. At Burnet’s conference with the Six Nations in 1724, he had succeeded in getting them to agree reluctantly to a trading house at Oswego, but not to a fort.

In Library and Archives Canada’s digital copy of the original minutes, the proclamation of September 2 1726 starts here.

into the record. In March, Claessen appeared before them and gave them his journal of his recent trip. The minutes describe “in substance” what it said, including a day by day account of how he went to several towns of the Six Nations and invited leaders to a meeting that was held in Seneca country beginning on February 22nd. The participants discussed the ongoing conflicts over the sale of alcohol in Iroquoia and other matters including an English boy taken captive from Virginia and thought to be held in Iroquoia. The Six Nations said they did not have the boy. They asked once again that the English prohibit the sale of alcohol in their country, but Claessen could only tell them once again that sales would be restricted to “Far Indians” from outside Iroquoia to promote the fur trade. The sachems described how alcohol was leading to violence and other problems, even to murders. They gave Claessen a belt of wampum to take back to the English authorities to confirm their position that it should be banned completely. However they agreed not to molest the traders or the far Indians.

into the record. In March, Claessen appeared before them and gave them his journal of his recent trip. The minutes describe “in substance” what it said, including a day by day account of how he went to several towns of the Six Nations and invited leaders to a meeting that was held in Seneca country beginning on February 22nd. The participants discussed the ongoing conflicts over the sale of alcohol in Iroquoia and other matters including an English boy taken captive from Virginia and thought to be held in Iroquoia. The Six Nations said they did not have the boy. They asked once again that the English prohibit the sale of alcohol in their country, but Claessen could only tell them once again that sales would be restricted to “Far Indians” from outside Iroquoia to promote the fur trade. The sachems described how alcohol was leading to violence and other problems, even to murders. They gave Claessen a belt of wampum to take back to the English authorities to confirm their position that it should be banned completely. However they agreed not to molest the traders or the far Indians.