Blocked from Trading with Montreal, Albany Traders Move West

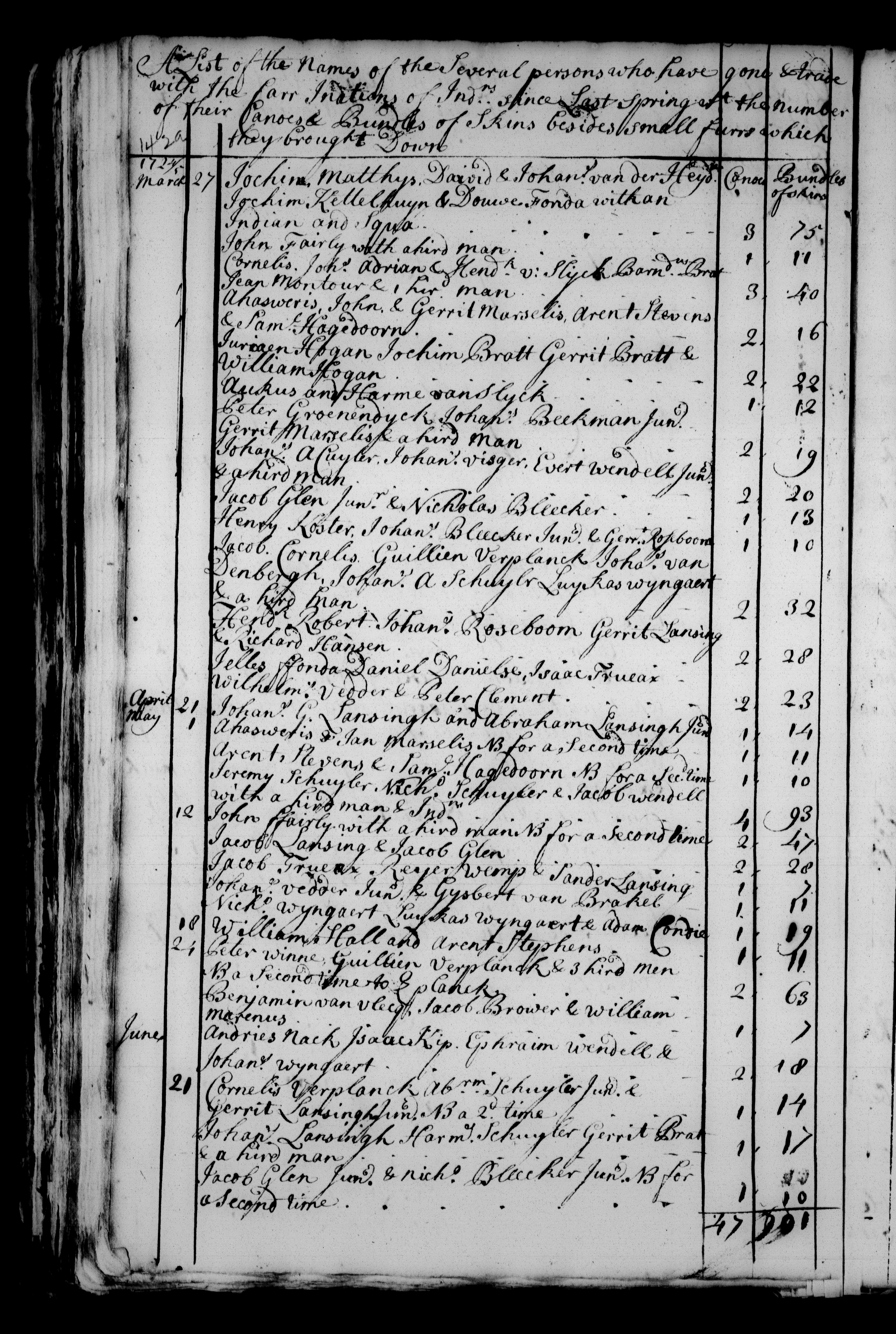

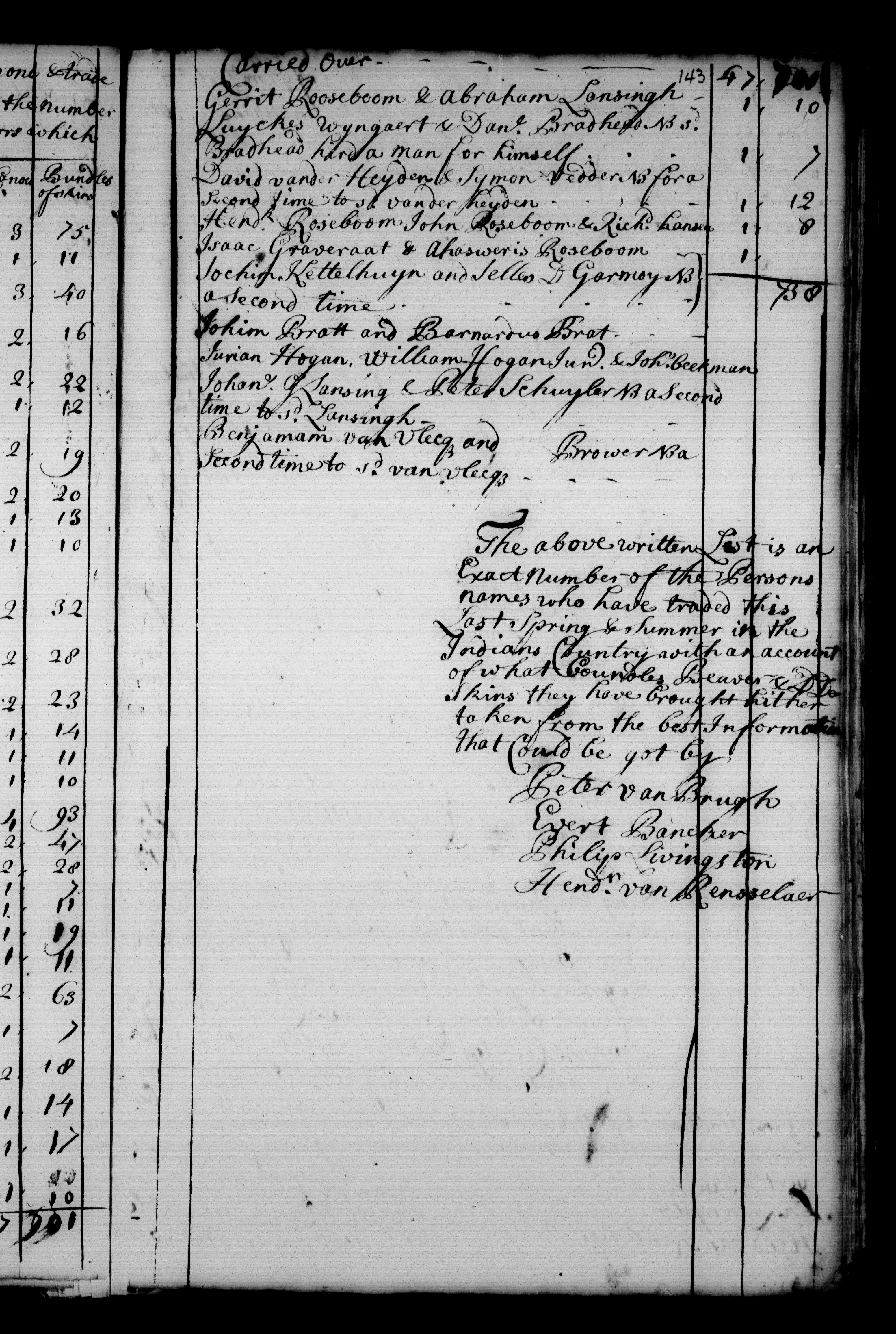

In September the commissioners made good on their promise to give the governor an account of the volume of the fur trade to the west. Captain Harme Vedder, stationed in Seneca Country, returned with his company and 50 bundles of fur. Many other traders were now going west as well. Despite the difficulties involved, the commissioners put together a detailed list of who had gone to Indian country and how many furs and skins they had purchased. At least fifty-one canoes, each carrying several traders, had been to the lakes and returned with 738 bundles of furs. The list of names covers many if not most Albany families. It also includes an unnamed Indian couple, several unnamed hired men, and a member of the versatile Montour family, Jean Montour. Some traders went more than once and some trips for which details were not provided brought 50 additional bundles of furs. In addition, 43 canoes of “far Indians” came to Albany and Schenectady with 200 bundles.

The direct trade from Albany to Canada was far smaller, as estimated by the commissioners and Lieutenant Blood, who was stationed at the English garrison at Mount Burnet, on the Hudson north of Albany.

Commerce between Albany and Canada continued however. On September 6th, Colonel Myndert Schuyler and Captain De Peyster returned from Canada and took the oath required of persons suspected to have traded with the French, which strongly suggests that they had in fact traded with the French. Moreover they confirmed that they had seen large quantities of strowd blankets sent from Albany to Montreal.

Trade with Montreal is Illegal, But News from Montreal is Valuable;

Grey Lock is Raiding New England

Schuyler and De Peyster also brought important news. A party of 150 warriors had left Montreal on their way to attack New England, passing Chambly, where others were encamped who planned to go as well. The French, including their priests, were encouraging them to fight, and Montreal was fortifying itself with a stone wall. The commissioners informed both New York Governor Burnet and the government of New England about the situation. In a subsequent letter they told Governor Burnet that the party at Chambly had been persuaded to go home instead of attacking New England, but the party of 150 from Montreal were sill out fighting. Two small groups of nine and fourteen were supposed to be lurking on the western frontiers, lead by Grey Lock (Wawenorrawot). The commissioners told Governor Burnet that the Indians were tired of war and wanted peace, but the French continued to push them to war.

The Six Nations Meet with the French

Schuyler and De Peyster said that a large group of leaders from the Six Nations had come to Montreal, where they were honored with a cannon salute. According to some Seneca leaders who came to Albany to tell the commissioners about the situation, and who had resolved not to go to Montreal themselves, the Six Nations contingent included eleven Seneca sachems from Canossodage and six from Onnahee. They went to condole the passing of “Lieutenant Governor” Monsieur “D Ramsay,” (Claude de Ramezay, the governor of Montreal who had died the previous summer.) Probably they also discussed their concerns about the escalating construction of forts in their country by both the French and the English.

Kahnawage, Rondax, and Schawenadie Want a General Treaty

Lieutenant Colonel Stephanus Grosbeeck had also been in Montreal. He told the commissioners that the sachims of Kahnawage and Schawenadie had sent him an express as he passed La Prairie, asking him by seven hands of wampum to bring a message that they were coming to Albany about October 1st, where they wanted to meet with the governors of New York and Boston (i.e. Massachusetts Bay) as well as the Six Nations. The commissioners contacted Massachusetts Bay Governor William Dummer directly to pass on this message, sending their letter by way of the authorities of Westfield Massachusetts, in order to inform them that they were at risk of attack.

The Six Nations Confirm the Treaty of 1722 with New York and Virginia

On September 26th, twelve sachems from Onondage, Cayuga, and Tuscarora came to Albany and met with the Commissioners. They said they had been sent to look into rumors spread among them and find a way to prevent such stories. They asked the Commissioners to read them the treaty made in 1722 between Virginia and the Six Nations, which was done.

Their speaker D’Kanasore (Teganissorens) gave a speech addressed to Asserigoa, the Iroquois name for the Governor of Virginia, asking the Commissioners to pass it on. He pointed out that the Six Nations had returned two prisoners taken in Virginia, an Indian (probably meaning Governor Spotswood’s Saponi servant) and a “Negroe boy,” (probably Captain Robert Hicks’ slave). He said that whoever was going fighting towards Virginia from Canada or from the Six Nations’ castles was doing it without their consent. Nonetheless, if they went past the line agreed to in the treaty of 1722 and were taken prisoner, they should likewise be returned.

Teganissorens also complained that the gunpowder they had purchased recently was defective. He asked for more powder as well as lead and gunflints, pointing out that the cost would be made up by the value of the skins they could obtain with it through hunting. He also asked for a smith as soon as possible, one better than those who had been working there, whose work was not the best.

The Six Nations Have New Objections to Burnet’s Trading House

Like the delegation from Kahnawake and Schawenadie, Teganissorens was not happy with Governor Burnet’s proposal for a trading house on the Onnondage (Oswego) River. He admitted that the Six Nations had consented to it, but he said they now feared it would cause mischief because alcohol would be sold there. People would get drunk, become unruly, and and cause harm. In addition some would likely buy rum instead of ammunition. Teganissorens asked that in the future traders would bring powder and no rum. A slightly different version of this speech was written out and then crossed out. It appears on page 146a.

The Commissioners responded the next day in a speech that verged on being abrupt, even rude. They told the delegates they were glad they wanted to prevent rumors from spreading; the only way to do so was simply refuse to listen to those who tried to delude them. They promised to convey Teganissorens’ speech to the Governor of Virginia, but added that the Six Nations should not let their people go past the boundary line agreed to in 1722. The people of Virginia “will never molest you if you do not excite them to it” and if you commit mischief you will have to answer for it, as also for “those for whom you are become Security.” The reference was to Kahnawake and its allies, the “French Indians.”

In response to the complaint about powder, they said they were sorry the Six Nations were too impoverished to buy enough powder to meet their needs. The Commissioners would ask the governor to write to England to have better powder made, but the real reason for their poverty was that they went fighting against people who had not attacked them. Instead they should stick to hunting. They agreed to convey the request for a smith and expected the governor would send one.

In response to the Six Nations’ request that traders bring powder rather than rum to sell on the Onondaga River, the Commissioners would only say that they would ask the governor to prevent traders from selling rum to the Six Nations and to sell them powder and lead. However, the traders would continue selling rum to the Far Indians because otherwise they would be unable to sell their goods. They urged the delegates to be kind to all traders on the Onondaga River and the lakes and to invite the far Indians to come trade with Albany in order to get goods cheaper than from the French. To encourage this they agreed to supply them with power, lead, and flints to meet their present needs.

The Six Nations added that the bellows at Onondaga was old and not fit for service. They asked for a new one before winter set in. They said they expected their speech to go to the governor of New York and then be forwarded to Virginia, acknowledged that the commissioners had asked them to keep the Treaty, and said they expected Virginia and its Indian allies to do the same. They expected that those who brought evil reports to them (that is rumors) probably did the same with the governor of Virginia, so they hoped he would not listen. They agreed to be kind to traders in their country and assist them however they could.

The commissioners asked what Monsieur Longuiel said when he came to their country, and Teganissorens quoted him at length. “Fathers, [the Six Nations had adopted Longueuil as their “child”] I desire that you be not surpriz’d when any blood shall be shed on the Onnondage River or at the side of the Lake for we and the English can’t well abide one another, do you not meddle with the Quarrel butt Set Still smoke & be neuter.” Tegannisorens confirmed that they had sent wampum to Canada to answer the governor saying they were surprised that the French should “trample on the Blood of their Brethren” in the Six Nations country. If they wanted to fight, they should “go to sea and fight where you have Room.”

Kahnawage, Rondax, and Schawenadie Appear, Expecting the General Treaty; They Offer an Indian Woman to Make Up for the Murder of a Soldier

Prior to the commissioners’ response to Teganissorens, seven sachems from Kahnewake, Schawenadie and Rondax appeared. They said they had come to meet with the governors of New York and Boston, as they had requested in the message they sent by Stephanus Grosbeeck a few weeks earlier. They expected the commissioners to provide lodging in Albany in the meantime. They had no wampum, for which they asked to be excused. The commissioners provided them with housing and necessities.

On September 28th, they formally condoled the man murdered at Saratoga by their people, presumably the English soldier named Williams from the garrison at Mount Burnet. They asked for reconciliation and forgiveness and gave wampum to wipe off the tears of those in mourning for him. And in addition they offered the commissioners a captive, an Indian woman, in place of the man they had lost. They said it was “not our maxim to do so yet we do it to satisfie you for the breach that is comitted.”

They said those who killed the soldier had been on their way to fight in New England. Their young men were unruly and could not be prevented from going to help the Eastern Indians fighting against the English. They asked the Commissioners to do everything they could to end the war.

The Commissioners explained that they had gotten the wampum message that Kahnawage, Rondax, and Schawenadie wanted to meet with the governors of New York and Massachusetts Bay and had sent notice to Boston. The governor there had said that he had to attend a treaty there with the Indians who were at war and asked the Commissioners to hear on his behalf what Kahnawage, Rondax, and Schawenadie had to say. The sachems said they would do so only if Colonel John Schuyler were present to represent Massachusetts. The Commissioners said that Colonel Schuyler was welcome to attend, but they did not think he would come. If the sachems did not want to deliver their message to the Commissioners to pass on to him, perhaps they could meet with him alone, or perhaps they would like to go to Boston, where they would be well received.

The next day the Commissioners gave a more full answer, reproaching the sachems for the murder of the soldier when the parties were at peace. They accused them of deliberately breaching the Covenant Chain in order to undermine the good relations between them. Those who committed such murders should be punished. But since the sachems had come to “mediate and reconcile” the matter, the commissioners said they would ask the governor to forgive the injury on condition that the sachems agree to deliver over anyone who committed such an offense in the future. They accepted the woman in place of the dead soldier “as a Token of your Repentance and sorrow for what is past” and gave a belt of wampum. After harangueing them further to the same effect, they gave them additional wampum. The sachems responded that they had heard the message and would communicate it to their leaders at home, since they were not empowered to promise to deliver up people who transgressed in the future.

The Commissioners wrote to the governor of Massachusetts Bay and described the meeting. They referred the governor to Colonel John Schuyler for more information, explaining that the sachems had refused to deliver their message except to him. They wished the governor success in making peace.

In Library and Archives Canada’s digital copy of the original minutes, September 1725 starts here at page 142 through 152a and jumps back here to p. 113.