During the early 1700s, the term “Schoharie” was used to refer to multiple communities, both European and Native American, living in close proximity along Schoharie Creek in the vicinity of the New York State town presently known as Schoharie. They included Mohawks as well as people from other Indigenous nations and Palatine Germans. On March 22, 1729, the Indian Commissioners met with Mohawk leaders Hendrick and Arie and a group of three Indians from Schoharie as well as “others of Sundry Nations.” The subject was a murder that had occurred the previous year. The commissioners were now working with the Mohawks to resolve the situation. Significantly, the commissioners did not try at any point to have the murderer or murderers turned over to the English authorities. Thus they implicitly acknowledged that Schoharie was within the jurisdiction of the Mohawks, not the English.

The commissioners told the perpetrators that they had had multiple complaints about their behavior toward the “Christians” at Schoharie, accusing them of causing trouble wherever they went, and of threatening to break the peaceful relationship between the English and the Six Nations. By “Christians” the Commissioners probably meant the Palatines, although most of the Indians living on Schoharie Creek were also Christians, so it is hard to be sure. The victim of the murder is described as “one of your brethren,” but since all the participants in the covenant chain called each other brethren, this term could apply to a person of any ethnicity.

The commissioners said they had kept the matter secret from the governor, hoping the Schoharie community would behave better in the future, but could do so no longer. As they said, “this blood lies yet on Earth and will Cry for Revenge Wherefore wee desire you to remove your Settlements in the woods beyond any Christian Plantation, that no mischiefe may Follow from your Insolent behaviour towards your brethren of the Six Nations. So that what mischiefe be done for the Future Shall be demanded off your hands.” These somewhat enigmatic words suggest that the perpetrators of the crime were not Mohawks, but people from elsewhere living at Schoharie with the permission of the Mohawks. They had offended the Six Nations as well as the English.

In order to prevent the people who had been complaining to the commisioners from taking revenge on their own and further escalating tensions, the commissioners asked the group involved in the murder to find another place to live. The Indians replied that they would not settle “Alone on the Christian Settlements” because some of their people, resentful about being made to leave, might attack the Christians and provoke more violence. Instead they agreed to relocate to their “native Countrey Cayouge and Oneyde.” They admitted that they should have “reconciled” the murder and said that the Sachems would do it, pointing out that it was done “in drink.” Finally they reminded the commissioners of the principle, often reiterated at treaties, that when individuals committed crimes, the Covenant Chain should not be broken. Instead the leaders of their respective communities should meet to resolve the situtation, as happened in this case.

The Schoharie Mohawks, by John P. Ferguson, is a good place to start in learning more about the Mohawk presence there. It is published by the Iroquois Indian Museum, located near Schoharie Creek at Howes Cave, NY, and available from their website.

In Library and Archives Canada’s digital copy of the original minutes, the entry for March starts here on p. 281.

[There are no entries for January 1729.]

[There are no entries for January 1729.]

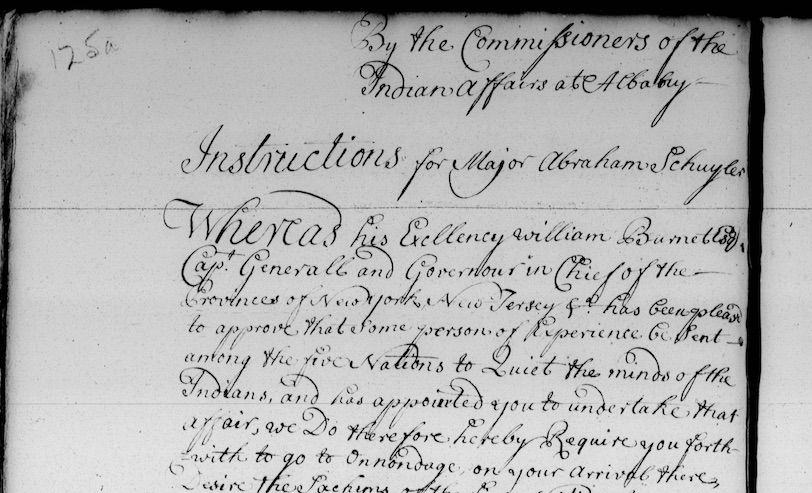

into the record. In March, Claessen appeared before them and gave them his journal of his recent trip. The minutes describe “in substance” what it said, including a day by day account of how he went to several towns of the Six Nations and invited leaders to a meeting that was held in Seneca country beginning on February 22nd. The participants discussed the ongoing conflicts over the sale of alcohol in Iroquoia and other matters including an English boy taken captive from Virginia and thought to be held in Iroquoia. The Six Nations said they did not have the boy. They asked once again that the English prohibit the sale of alcohol in their country, but Claessen could only tell them once again that sales would be restricted to “Far Indians” from outside Iroquoia to promote the fur trade. The sachems described how alcohol was leading to violence and other problems, even to murders. They gave Claessen a belt of wampum to take back to the English authorities to confirm their position that it should be banned completely. However they agreed not to molest the traders or the far Indians.

into the record. In March, Claessen appeared before them and gave them his journal of his recent trip. The minutes describe “in substance” what it said, including a day by day account of how he went to several towns of the Six Nations and invited leaders to a meeting that was held in Seneca country beginning on February 22nd. The participants discussed the ongoing conflicts over the sale of alcohol in Iroquoia and other matters including an English boy taken captive from Virginia and thought to be held in Iroquoia. The Six Nations said they did not have the boy. They asked once again that the English prohibit the sale of alcohol in their country, but Claessen could only tell them once again that sales would be restricted to “Far Indians” from outside Iroquoia to promote the fur trade. The sachems described how alcohol was leading to violence and other problems, even to murders. They gave Claessen a belt of wampum to take back to the English authorities to confirm their position that it should be banned completely. However they agreed not to molest the traders or the far Indians.